SHD/GR 21 YC 171 - "service registers for non-commissioned officers and enlisted men of the line infantry (1802 to 1815)". LW is in YC 171. (Is YC a battalion within a regiment? Is GR group?)

For future reference, for any service person in France...

...the following is available. This is a difficult site, use a webpage translator if you need one...

The sets of records available include: Personnel registers of the

Ancien Régime (1682-1793); Service registers of non-commissioned officers and enlisted men of the

Imperial Guard (1799-1815); Service registers of non-commissioned officers and enlisted men of the

Line Infantry (1802-1815).

|

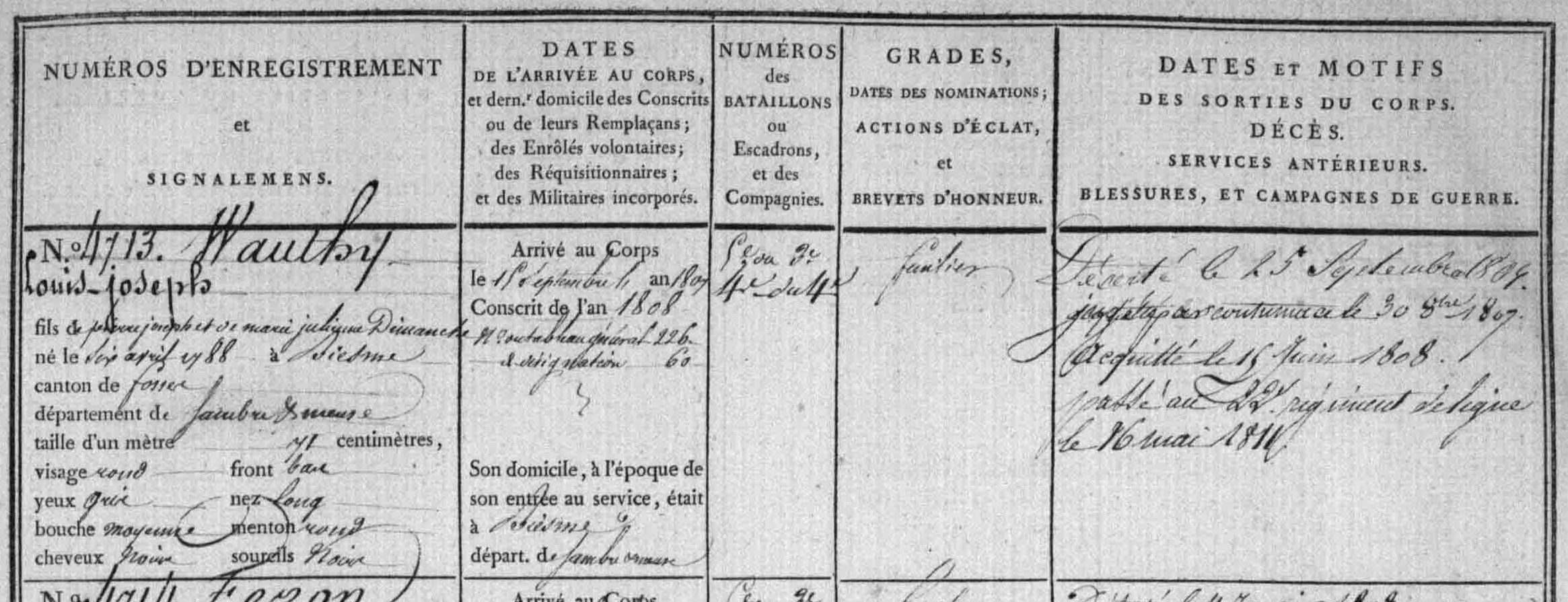

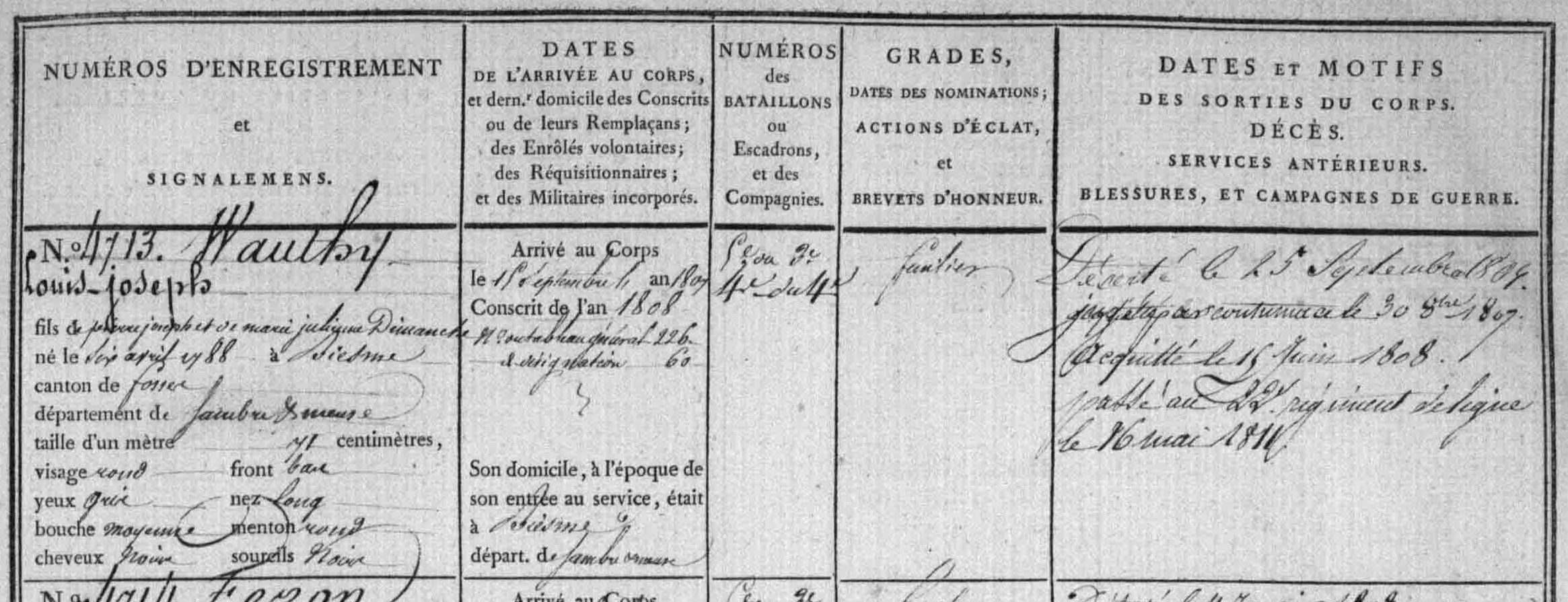

The full page this was taken from is available at this external link (page numbered 287, it is the 290th page of the 554-page set). And it is also stored locally on this site. Pages 1 through 3 of this document set are bureaucratic instructions for filling out the forms. Notably, page one states that these registrants are for the "19 régiment d'infanterie de ligne" (19th Line Infantry Regiment). 6 records per page ending on full page 503, or 500 pages of registrations, but the last registration number is 5,973 so there must be some incomplete pages. (After a brief investigation, having two registrations numbering 3,755 and two numbered 3,756 doesn't help.) Page 504 has a form that looks like it is relieving someone of their duties. The last 49 pages have the surnames grouped by first letter, with the groups in alpha sequence.

| Taille (height) : |

1.71 meters |

(5' 7") |

(average) |

| Visage (face) : |

rond (round) |

Front (forehead) : |

bau, ban, bas (low)? |

| Yeux (eyes) : |

grise (grey) |

Nez (nose) : |

long (long) |

| Bouche (mouth) : |

moyenne (medium, average) |

Menton (chin) : |

rond (round) |

| Cheveux (hair colour) : |

noir (black) |

Sourcils (eyebrows) : |

noir (black) |

Besides this subjective description, the record does show Louis Joseph Wauthy was 1 meter 71 centimeters tall, not quite 5' 7". The average male height in many European countries at the time was around 5' 5" to 5' 7" for common men. Nutrition, the availability of good food, and having the means to acquire it played a part.

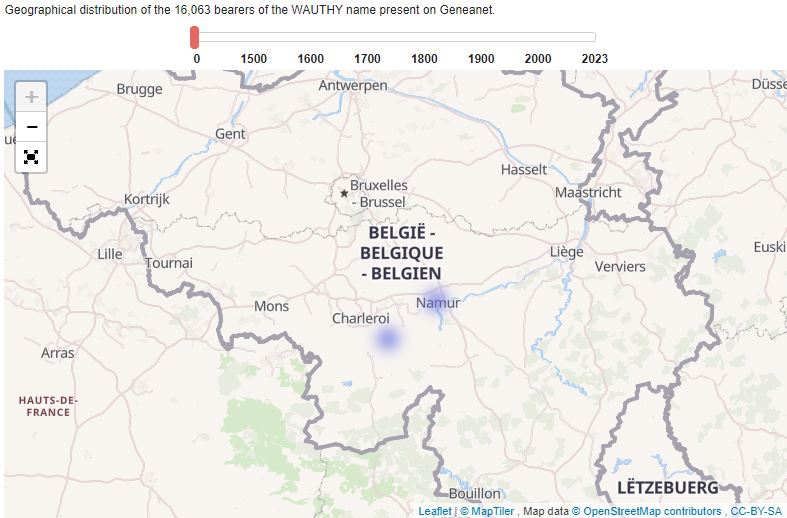

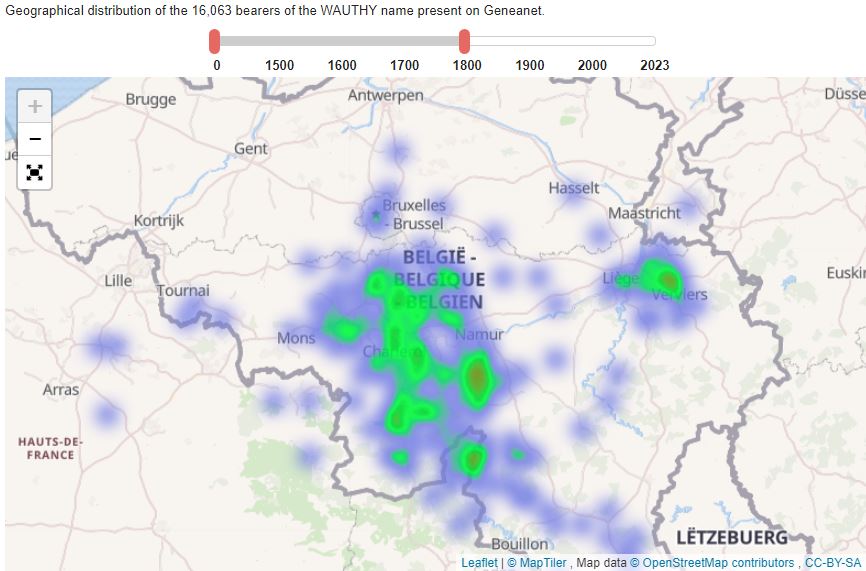

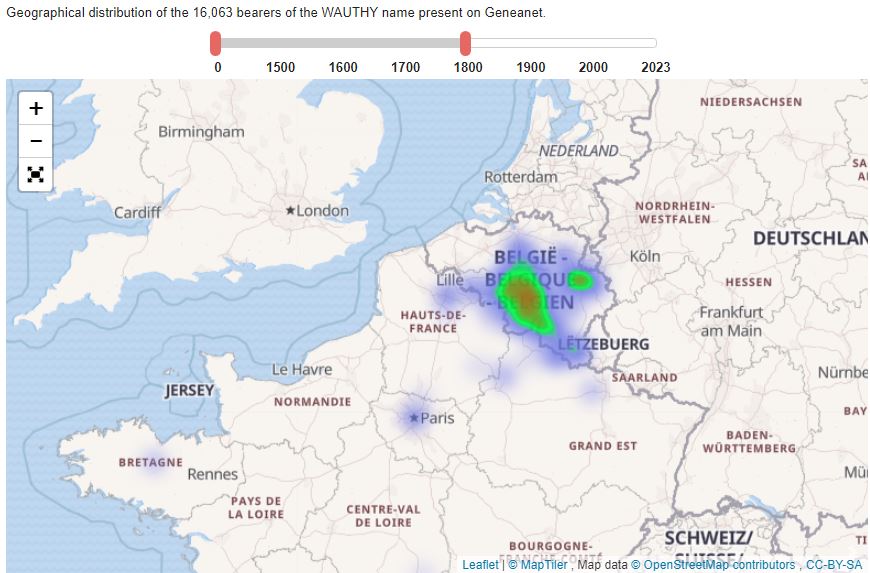

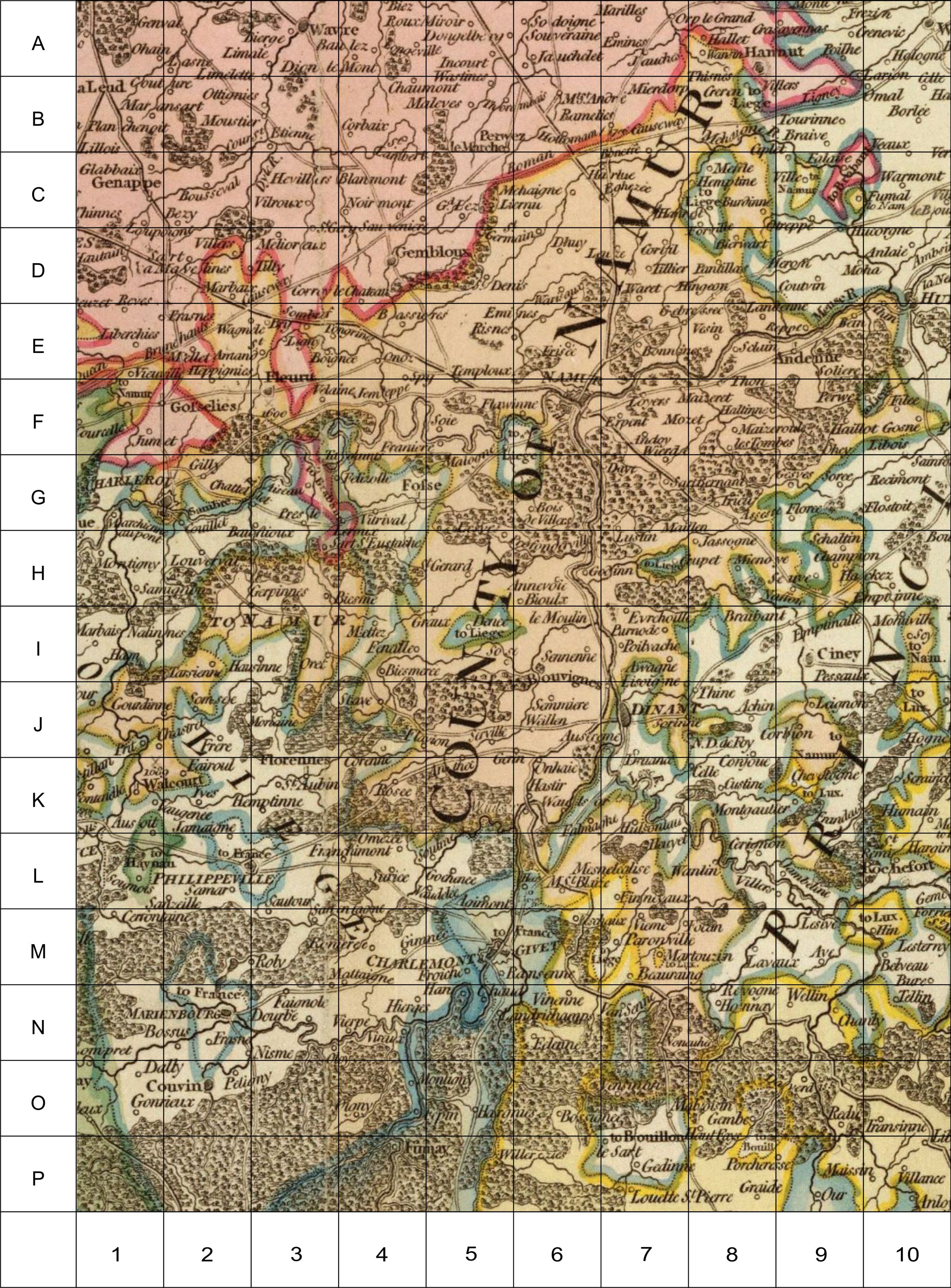

Below his name is written: "fils de (son of) Pierre Joseph (Wauthy) et de Marie Julienne Dimanche". "né (born) le six avril 1788 à Biesme, canton de Fosses-de-Ville, department de Sambre & Meuse". A canton was a subdivision of a department.

The department of Sambre-et-Meuse is a former French administrative district whose capital was Namur. Created in 1795, dissolved in 1814, this coincides with the occupation of Wallonia by French forces.

"Dates of arrival in the corps, and last residence of the conscripts or their replacements; voluntary enlistments; requisitioners; and incorporated soldiers." "Battalion or squadron, and company." In the column "Ranks, dates of nominations, actions of brilliance (perhaps heroism), and certificates of honor", what would make sense here would be the word fusilier, or rifleman, a fusilier referring to a soldier armed with a fusil, a type of musket or flintlock firearm.

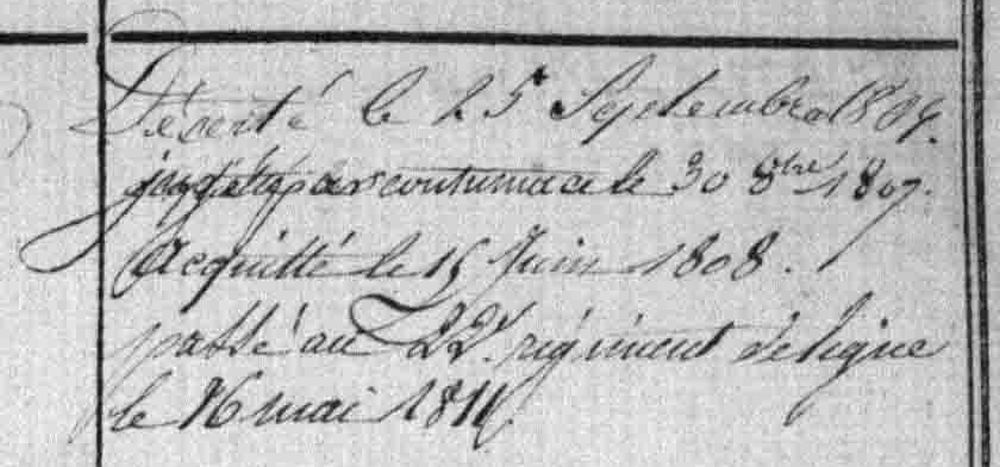

In the column that may translate as: "Dates and Reasons for Excursions of the Corps. Death. Previous service. Wounds and war campaigns.", are details about LW deserting just 24 days after arrival.

This is the portion of the record that describes the desertion. Translated with assistance from MW: "Deserted September 25th, 1807. Judged in absentia October 30th, 1807. Acquitted June 19th, 1808." Different people made entries, it seems, which is why the handwriting is not uniform.

Why did he desert, and why was he acquitted? Both questions might be answered by the early death of his father.

"Pierre Joseph Wauthy died December 12, 1807, in Biesme, Mettet, Namur, Belgium, at age 53."

LW had just arrived on September 1st, and 24 days later he deserts. If his father had a serious sudden illness come upon him, like a heart attack or cancer, LW might have got wind of it and tried to get home.

The text goes on to say "jugé par contumace" (judged in absentia) October 30th, 1807. This may mean that LW hasn't been arrested yet or the judgment was handed down "in absentia", without legal representation or testimony by the accused. (This appears to have been overwritten on the words "acquitté le", as if the next line was being written in here out of turn.

ChatGPT: "Trial in absentia: If an accused soldier refused to attend the court-martial, was deemed unfit to stand trial due to illness or other reasons, or simply couldn't be brought to the trial for logistical reasons, (a trial) could proceed in their absence."

Being acquitted June 19th, 1808 may have cleared LW's name, but there is nothing conclusive yet to say he has returned to service until the next line, which appears to say that LW has been "passé au 22nd régiment de ligne", translated as "transferred to the 22nd Line Infantry Regiment", on May 16, 1811. Being transferred was not an individual event (i.e. not a personal request). Others in his unit have the exact same entry in their records.

While it first appeared that the 1807 desertion is the anticipated desertion of a Feuillen Wauthy descendant who would go on to change his name to Thibeau, this is not so. LW is still in the French Army, name unchanged.

In his brief time at large, LW would have experienced the difficulties in moving about as a fugitive. Anyone of his age would be expected to be in the army. One couldn't just walk about in uniform. Each man carried "livrets", identification papers, that would not be easily replaced or forged. He would have needed an alias. There would likely have been checkpoints on roadways and roving patrols. There may have been witnesses, people that LW told what he was about to do before he left camp. He would need food and shelter. His likely destination would be known. All of this would have contributed to quick capture.

ChatGPT: "During the Napoleonic era, French people typically carried identification papers known as "livrets." Livrets were small booklets or passports that served as personal identification documents. These identification papers were introduced during the French Revolution and continued to be used throughout the Napoleonic era.

Livrets contained essential information about the individual, such as their name, age, occupation, place of birth, and physical characteristics. They also included details about the person's nationality and sometimes their residence or travel permissions. Livrets were issued by local authorities, and citizens were required to carry them as a means of identification and to prove their identity when necessary.

Livrets were particularly important for military personnel, as they served as military identification documents and recorded an individual's service history, unit, and rank. For soldiers, the livret also contained records of their promotions, campaigns, and other military achievements.

Carrying a livret was mandatory in France during the Napoleonic era, and failure to present one when requested by authorities could lead to suspicion or legal consequences. The use of livrets was part of the French government's efforts to maintain control over the population, ensure security, and enforce conscription and military service during the tumultuous times of the Napoleonic era."

Three years in the 19th...

Initially, Louis Joseph Wauthy would have been instructed to report somewhere to begin his training. While there was a large center known as the Boulogne Camp on the Channel coast about 30 km from Calais that was training soldiers for a planned invasion of England, it is more likely that LW would have been told to report to a much smaller camp for new recruits closer to his home. Once basic training had been completed and he had been assessed and pronounced fit and ready, he would have been transported with others, or would have marched with others, to wherever his regiment was located at that time.

Napolun.com: "the mainstay of the French army throughout the Napoleonic wars was the long-suffering, hard-marching infantry regiments and battalions".

So, where was the 19th Line Infantry Regiment from June 19th, 1808 when Louis Joseph Wauthy was acquitted until May 16th, 1811 when he was transferred to the 22nd Line Infantry Regiment?

Regimental war records for the 19th Line Infantry Regiment can be found here: Battles and Combats.

Wikipedia: "In 1809, the French military presence in the Confederation of the Rhine was diminished as Napoleon transferred a number of soldiers to fight in the Peninsular War."

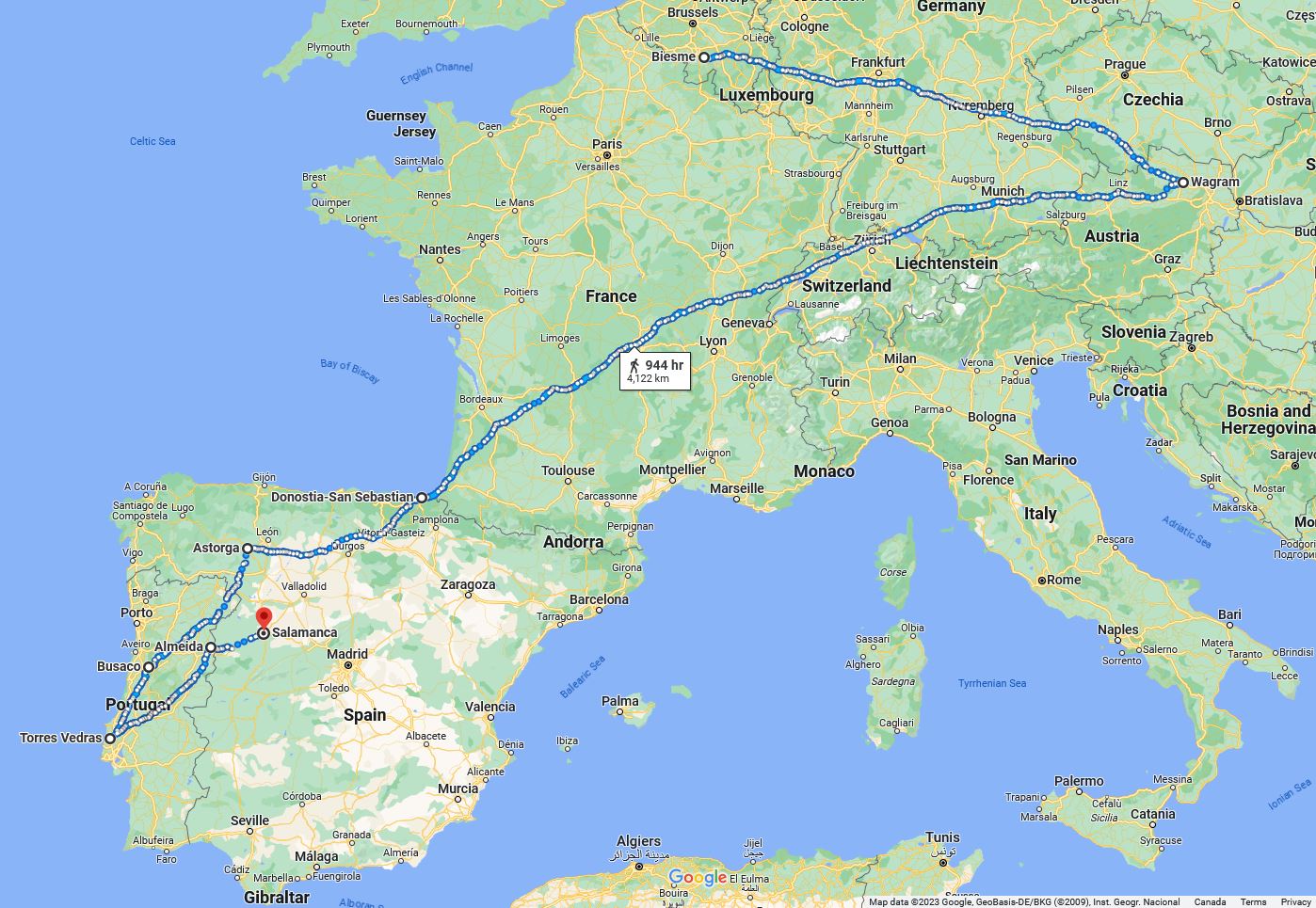

LW may have seen action in the theatre of the Confederation of the Rhine (Wagram, July 4th, 1809) before being relocated to participate in the Peninsular War with Spain and Portugal.

ChatGPT: "The 19th Line Infantry Regiment (first) arrived in the Iberian Peninsula in 1808 as part of the French forces sent to support Napoleon's brother, Joseph Bonaparte, who had been installed as the King of Spain. Their presence was met with resistance from Spanish and British forces." "The regiment likely participated in various early engagements during the Peninsular War, including battles and skirmishes against Spanish guerrillas and British forces. These early years of the war saw a series of clashes as the French sought to establish control."

Notable events in 1810 include...

Astorga (Spain), April 20th, 1810. This appears to be a reference to the French forces taking Astorga initially. Wikipedia: "Astorga was located on the flank of the French invasion of Spain and Portugal, and was meant to be used as a headquarters during the campaign. For several weeks no attack took place, as neither side had artillery enough to fight well. Shortly after the French guns arrived, however, a hole was made in the wall and the city fell shortly thereafter. The French overpowered the Spanish garrison inside and took the city on April 20, 1810; with a loss of 160 men." What is known as the Siege of Astorga took place in 1812, a Spanish victory. More below...

Siege of Almeida (Portugal), July 25th, 1810. Wikipedia: "In the siege of Almeida, the French corps of Marshal Michel Ney captured the border fortress from Brigadier General William Cox's Portuguese garrison. This action was fought in the summer of 1810 during the Peninsular War portion of the Napoleonic Wars. Almeida is located in eastern Portugal, near the border with Spain." For details about the retaking of Almeida, see below.

Battle of Busaco (Spain), September 27, 1810. See painting below. Wikipedia: "Having occupied the heights of Bussaco (a 10-mile (16 km) long ridge located at 40°20'40"N, 8°20'15"W) with 25,000 British and the same number of Portuguese, Wellington was attacked five times successively by 65,000 French under Marshal André Masséna. Masséna was uncertain as to the disposition and strength of the opposing forces because Wellington deployed them on the reverse slope of the ridge, where they could neither be easily seen nor easily softened up with artillery. The actual assaults were delivered by the corps of Marshal Michel Ney and General of Division (Major General) Jean Reynier, but after much fierce fighting they failed to dislodge the allied forces and were driven off after having lost 4,500 men against 1,250 Anglo-Portuguese casualties. However, Wellington was ultimately forced to withdraw to the Lines of Torres Vedras after his positions were outflanked by Masséna's troops."

The Lines of Torres-Vedras (Portugal). Wikipedia: "The Lines of Torres Vedras were lines of forts and other military defences built in secrecy to defend Lisbon during the Peninsular War. Named after the nearby town of Torres Vedras, they were ordered by Arthur Wellesley, Viscount Wellington, constructed by Colonel Richard Fletcher and his Portuguese workers between November 1809 and September 1810, and used to stop Marshal Masséna's 1810 offensive." National Army Museum: "In 1810, a large French army under Marshal Masséna captured the border fortresses of Ciudad Rodrigo and Almeida, and advanced into Portugal. On 27 September, Wellington's Anglo-Portuguese army checked them at Busaco. The French were driven off with the loss of 4,500 killed or wounded, compared to Anglo-Portuguese losses of about 1,250. Wellington's men then fell back behind the Lines of Torres Vedras. These defences were strengthened by a scorched earth policy to their north, which destroyed food stores and anything else useful to the French. Wellington's position was clearly impregnable. But it took Masséna six months, and the starvation of 25,000 of his men, before he decided to retreat."

This would see the French forces held outside of Lisbon until their retreat in the spring of 1811. This does seem to coincide with LW's transfer to the 22nd Line Infantry Regiment on May 16th, 1811. LW may have been one of many who were transferred to the 22nd to bolster their numbers for continued fighting in Spain. The battle of Albuera occurred on the same day suggesting the 22nd was either at that battle or the shuffle of troops involved more than just these two regiments. With the 19th withdrawing from the Lisbon area and the 22nd withdrawing from southern Spain, the transfer may have occurred somewhere along the way, perhaps near Salamanca where the 22nd would be the following year.

The 19th was pulled from Spain and is on record for being in Jacobouwo (Poland), Polostk and Borisow in 1812; Dresden and Leipzig in 1813; and Brienne, Monterau and Bar-sur-Aube in 1814 before ending the war at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. The 19th could have been replenished in 1811 with new recruits after returning to France, to make up for losses in Portugal and for those transferred to the 22nd.

|

A painting by Charles Turner, Battle of Sierra de Busaco above St. Antonio de Cantaro, September 7th, 1810. Yale Center for British Art.

|

This illustration gives an idea of what a battlefield might have looked like. Highly visible Redcoats (English) and Bluecoats (French) in lines of fixed-bayonnet musket-firing infantry in all-weather open terrain near fortified positions. Insane heroic behaviour. Nothing like the trench warfare of WWI or the aircraft-centric warfare WWII evolved into. Today, weaponry reaches enemies often not seen with the naked eye, with terrifying force. One man with a modern military precision weapon could kill a hundred line infantrymen before they could get off a single inaccurate shot.

From the informative Ontario archives site about the War of 1812 in Canada... "The standard tactics used by the British infantry at this time was the line of battle. Men stood in two lines, shoulder to shoulder, and fired their smooth bore muskets in disciplined volleys. This tactic was dictated by the inaccuracy of the standard "brown bess" musket, and the need to achieve concentrated fire against a similar line of enemy troops. Also, a 19th century battlefield was a confused place. The muskets and artillery discharged a heavy white smoke that obscured opponents and messages from a commander to specific parts of the line could only be transmitted in writing or orally. It was not unusual for this "fog of war" to take control of the battlefield from the commanding officers and place it in the hands of chance and the individual soldiers. Theoretically one side would give way before the musketry or a final bayonet charge.

The fire of the infantry would be supplemented by light field artillery, these guns were identified by the weight of shot fired, from 3 pounds to 12 pounds, which were designed to batter defences or cut through the enemy infantry. At close range the guns could be loaded with "cannister" which turned them into large shotguns, spreading dozens of small iron balls or fragments in a wide path. First Nations warriors were employed as light troops which sought to turn the flank of an opponent."

Transferred to Napoleon's 22nd Infantry Line Regiment in Spain, May 16th, 1811...

In 1811, the 22nd Regiment, as part of the French occupying forces, would have found itself increasingly on the defensive as Wellington pushed the French out of Portugal and launched an invasion of Spain.

ChatGPT, paraphrased: "The British and Portuguese forces, with the support of Spanish allies, were implementing a strategy of attrition, gradually wearing down the French through a combination of defensive actions and periodic offensive operations.

The retaking of Almeida (Portugal), by the Allies, in May 1811. ChatGPT: "As part of their strategy to drive the French out of Portugal, the British and Portuguese forces embarked on a march towards the fortress town of Almeida, which had been under French control. The retaking of Almeida (eastern Portugal) took place (between April 14th amd May 10th, 1811), with British and Portuguese forces besieging the town. The siege eventually led to the capture of Almeida from the French."

Siege of Astorga (Spain), June 29th to August 19th, 1812. Wikipedia: "The Spanish troops of Lieutenant-General Francisco Gómez de Terán y Negrete, Marquess of Portago, started the operations, and laid siege to Astorga. The siege was part of the Allied offensive in the summer of 1812. The Spanish VI Army led by General José María Santocildes, by order of General Francisco Castaños, take the measures necessary for the recovery of Astorga. On August 18th, after a hard resistance, the French garrison surrendered to the Spaniards."

By June of 1812, Wellington was heading for Salamanca.

Battle of Salamanca (Spain), July 22nd, 1812. ChatGPT, paraphrased: "The Battle of Salamanca resulted in a decisive victory for the allied forces, primarily led by the Duke of Wellington's Anglo-Portuguese army. This victory was significant in itself, but it also boosted the morale of the allied forces. Salamanca was a strategically important city in Spain. It was a major transportation and communication hub, with several key roads converging in the region. Its capture allowed the allies to secure an important logistical and strategic center.

The Battle of Salamanca forced the French, commanded by Marshal Auguste Marmont, to retreat from the Spanish capital, Madrid. This marked a turning point in the Peninsular War, as it allowed the Spanish to reoccupy their capital and significantly weakened French control in Spain. The defeat at Salamanca was a cause of concern for Napoleon, who recognized the strategic importance of the region. It forced him to divert resources to the Iberian Peninsula, which had implications for his campaigns elsewhere in Europe.

After the battle, the allied forces pursued the retreating French armies. The victory at Salamanca set the stage for a successful allied advance into Spain and the eventual liberation of large portions of the country from French control. The Battle of Salamanca showcased the effectiveness of the British and Portuguese forces in the Peninsular War, led by Wellington. It enhanced their reputation and demonstrated their ability to defeat the French in open battle."

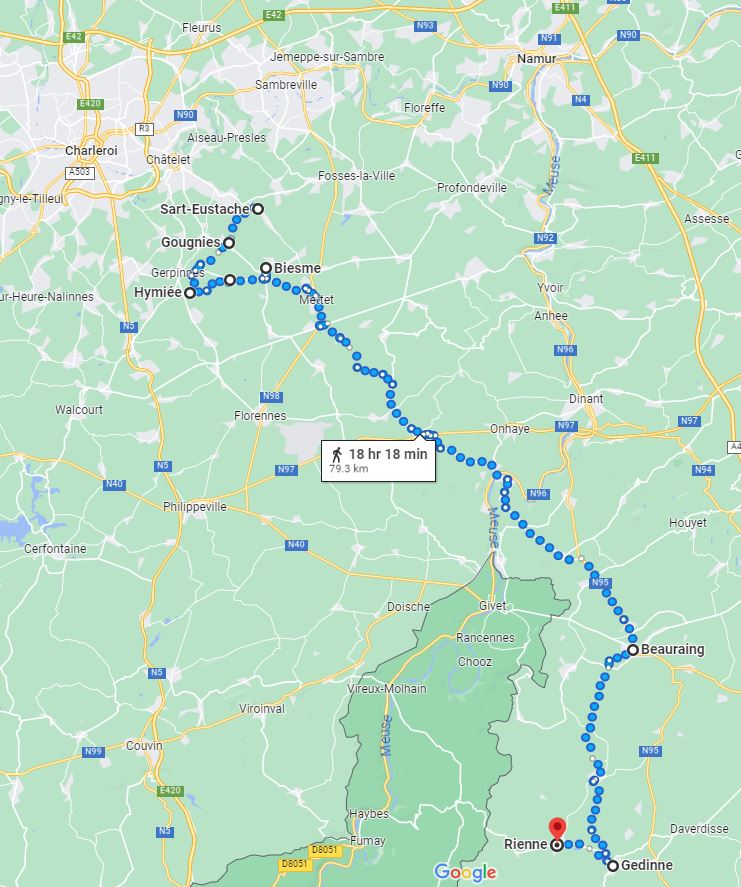

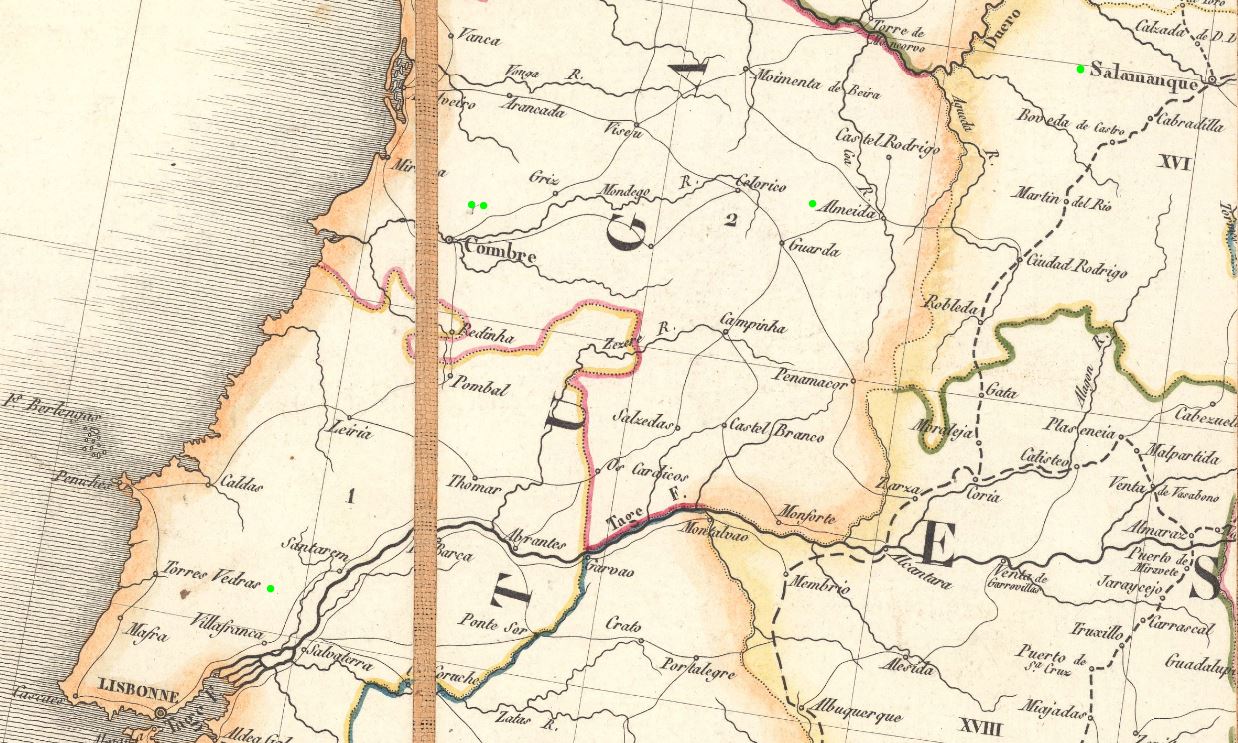

The left map shows the possible route taken by Louis Wauthy as part of the 19th and 22nd Regiments. There would be at least one other location in Wallonia he would have been at for recruit training. This is a walking route - Google calculates the distance to be 4,122 km over 118 days if they marched an average of eight hours a day. The last leg is undrawn as it might be confusing at first, the 22nd would have been retreating in the direction of San Sebastián following their ouster from Salamanca. There would be many more points and diversions along this route that would have extended the distance over the four years that brought LW to the siege of San Sebastián.

The right map is just a portion of a period map from 1813 showing points of interest in the Peninsular War. Torres-Vedras, Almeida, and Salamanca have green dots. Busaco does not appear on this map but its location is indicated with two green dots. Follow this link to view the full map online (David Rumsey Map Collection) to assist with overall geographical comprehension. (The full map is actually larger than the modern Google map shown here.) Use the navigation controls provided (position, zoom).

napoleon-series.org has a great deal of information on the Napoleonic Wars, including details on all of the French Infantry Regiments - regimental history, officers, regimental war record, battle honours, etc.

Regimental war record for the 22nd Line Infantry Regiment: Battles and Combats.

For the 22nd, their regimental war record shows that their next notable action following Salamanca was July 7th to September 8th, 1813, the siege of San-Sebastián, but there is a gap of a year between Salamanca and San Sebastián - what filled it?

ChatGPT: "After the Battle of Salamanca in 1812, which resulted in a decisive victory for the Allied forces led by the Duke of Wellington, the Allies pursued a series of military and strategic actions in the ongoing Peninsular War against the French in Spain. Here are some of the key actions taken by the Allies after the Battle of Salamanca:

Pursuit of the French: Following the victory at Salamanca, the Allies pursued the retreating French forces, led by Marshal Auguste Marmont. This pursuit aimed to disrupt and further weaken the French position in Spain.

Capture of Madrid: The Allies continued their advance into Spain and retook the Spanish capital, Madrid, in August 1812. This was a significant achievement as it allowed the Spanish government to return to the city.

Siege of Burgos: After capturing Madrid, the Allies laid siege to the city of Burgos, which was held by a French garrison. Burgos was about half way between Salamanca and San Sebastián. The siege, however, proved to be challenging, and the Allies were eventually forced to lift it on October 31st, 1812.

Retreat to Portugal: Due to logistical challenges and the approach of a large French army under Marshal Nicolas Soult, the Allied forces were compelled to retreat from Burgos and eventually withdrew back to Portugal.

Reorganization and Reinforcement: During the retreat, the Allies reorganized their forces and received reinforcements. The retreat allowed them to regroup and prepare for future operations.

In 1813, the Allies again reentered Spain, continuing their campaign against the French. The Battle of Vitoria in June 1813 was a decisive victory for the Allies, and it further contributed to the liberation of Spain from French occupation."

These actions would explain how the 22nd LIR took until the summer of 1813 to begin their next major named engagement following Salamanca. At first, the 22nd's retreat would coincide with the Allies' advances. Fresh French forces, though, would drive the Allies back to Ciudad Rodrigo, near the Portuguese frontier. By May 20th, 1813, after reorganizing and receiving reinforcements, the Allies were ready to confront the French forces again. Under Wellington, in an effort to outflank the French Army, an Allied force of 121,000 causing the French to retreat back to Burgos "with Wellington's forces marching hard to cut them off from the road to France". Burgos was as far as the Allies had advanced in 1812. Vitoria is about half way again to San Sebastián.

Battle of Vitoria (Spain), June 21st, 1813. The account at Wikipedia is quite compelling, worth the read. While the 22nd LIR may or may not have participated in this battle, its outcome affected them. "At the Battle of Vitoria... a British, Portuguese and Spanish army under the Marquess of Wellington broke the French army under King Joseph Bonaparte and Marshal Jean-Baptiste Jourdan near Vitoria in Spain, eventually leading to victory in the Peninsular War. Because they had marched 20 miles earlier in the day before the battle, and because the French had abandoned their "booty" (estimated value $100 million in today's money), the Allies did not pursue the French that day. The 22nd was at San Sebastián when the allies laid siege to it, perhaps having been installed there from as far back as the year before.

Siege of San Sebastián (Spain), July 7th to September 8th, 1813. ChatGPT: "Following the Battle of Vitoria, the British and Portuguese forces besieged the city of San Sebastián, which was held by the French. The city eventually fell to the Allies, contributing to their overall success in the campaign."

.

The Siege of San Sebastián. (Watch an 18-minute documentary about this battle, entitled The Peninsular War: The Siege of San Sebastián (1813) and...)

Maritimeheritage.org: "...By the summer of 1813 the Peninsular War had reached a crisis. The Port of San Sebastián had to be captured fast if Wellington's British armies were to avoid a humiliating retreat due to lack of supplies. But in San Sebastián was the wily French commander Louis Rey. The scene was set for a classic siege campaign.

The British, Portuguese and Spanish armies of Lord Wellington had defeated the French in Spain and were poised to invade France itself. But the supply situation was critical. All of Wellington's supplies had to come from Britain to Lisbon and were then carried over bad roads, mountain ranges and dusty plains for hundreds of miles to reach the fighting front. Wellington needed a port with good harbour facilities close to the battle front. There was only one available, but it was held by a French force under the command of General Louis Rey who was desperately repairing and reinforcing the defences. The siege began on July 7, 1813..."

Wikipedia: "In the siege of San Sebastián (July 7th to September 8th, 1813), part of the Peninsular War, Allied forces under the command of Arthur Wellesley, Marquess of Wellington failed to capture the city in a siege. However in a second siege the Allied forces under Thomas Graham captured the city of San Sebastián in northern Basque Country from its French garrison under Louis Emmanuel Rey. During the final assault, the British and Portuguese troops rampaged through the town and razed it to the ground."

Read a firsthand account of this time in The Journal of James Hale, by Sergeant James Hale, Ninth Regiment of Foot, published in 1826. Vitoria is first mentioned on page 104, San Sebastián on page 108.

Read a series of detail-rich volumes entitled History of The War in The Peninsula and in The South of France by W.F.P. Napier, C.B. Volume 6 has passages about the two sieges of San Sebastián in chapters I and III. PDF version is a selectable option that offers more control over the contents.

A sample passage, from page 233, about the acceptance of the loss of San Sebastián to the Allies and the leaving behind of the garrison holding the castle: "...in the course of the day (August 31st) general Rey's report of the assault on San Sebastián reached (Marshal General Jean-de-Dieu Soult), and at the same time he heard that general Hill was in movement on the side of St. Jean Pied de Port. This state of affairs brought reflection. San Sebastián was lost, a fresh attempt to carry off the wasted garrison from the castle would cost five or six thousand good soldiers, and the safety of the whole army would be endangered by pushing headlong amongst the terrible asperities of the crowned mountain." The French who were left to fend for themselves surrendered.

A second passage predicts the next phase of the war. "The fall of San Sebastián had given Lord Wellington a new port and point of support, had increased the value of Passages as a depôt, and let loose a considerable body of troops for field operations; the armistice in Germany was at an end, Austria had joined the allies, and it seemed therefore certain that he would immediately invade France."

The Library of Congress has a map/document entitled Plan of the siege of St. Sebastián in the year 1813. It is incredibly high resolution and contains great detail in both images and text. In part, it states: "Right Attack continued. Operations against Castle - Batteries opened 8th September. Enemy capitulated same day."

This section is relevant to the stories of both Jean Jacques (Jacob) Thibeau and Louis Joseph Wauthy. It has been put in this frame as a duplication and correlation point.

|

Two remaining battles in 1813 would see the French army retreating from Spain. LW's window of opportunity for arriving in Nova Scotia in 1814, to fit the "10 years in the province" as stated on the land grant petition, should have LW leaving the continent in late 1813 or early 1814.

Battle of the Pyrenees, Spain (1813): This series of battles took place in July and August 1813 along the Pyrenees Mountains as the French retreated from Spain into France. The battles were fought between the Anglo-Allied forces and the French, and the outcome was generally favorable for the Allies.

Battle of Nivelle, France (1813): In November 1813, this battle was fought between the Anglo-Allied forces and the French under Marshal Soult. The battle resulted in a victory for the Allies.